0

You have 0 items in your cart

Colonial Singapore, claimed for Britain by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819, soon became a cosmopolitan trading hub. Among the earliest communities to arrive were Armenians, joining others such as Chinese, Indians, British and the indigenous Malays. Many came from New Julfa, Persia (Iran). Though small in number, Armenians had a substantial impact in Singapore. The world-famous Raffles Hotel – home of the original Singapore Sling – was founded by the Sarkies brothers, whilst other members of the community co-founded The Straits Times newspaper. Today, the Armenian Apostolic Church, built in 1835, is the oldest surviving church in the city.

In this colonial setting lived Ashken Hovakimian, known in Singapore society by her Anglicised name, Agnes Joaquim. Born in 1854 to a prominent Armenian family, she was the eldest daughter of Parsick Hovakimian, a merchant and property owner who had arrived in Singapore in around 1840. During the nineteenth century, Armenians like Ashken’s family were treated on a par with Europeans and accepted into all aspects of colonial life in Singapore. This acceptance was partly because the Armenians formed such a small community that they were never perceived as a threat, but more importantly, because they were Christian.

The wealthy Armenian families were regularly invited to major balls, banquets, Government receptions, and other social events, while Armenian men served in prominent civic roles, joined European social clubs, and participated fully in the colony’s professional and political life. Though the Armenian community would face some prejudice and social marginalisation after the turn of the 20th century from the British, this did not begin in earnest during Ashken’s lifetime.

Above: Armenians in colonial-era Singapore, and the Armenian Apostolic Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator

Like her mother, Urelia, Ashken was a skilled plantswoman. She devoted herself to horticulture and orchid cultivation in the garden of her family home on Cairnhill Road. By the 1880s, she was regularly winning prizes at flower shows organized by the Singapore Agri-Horticultural Society. Records of her awards survive, and reveal she won them for both ornamental and edible plants, such as cucumbers and mangosteens.

At this time, it was common practice to grow orchids in pots which allowed easy transportation to flower shows. This is in contrast to the modern practice in tropical Southeast Asia of growing orchids bare root or mounted directly onto trees, which only became widespread after World War II.

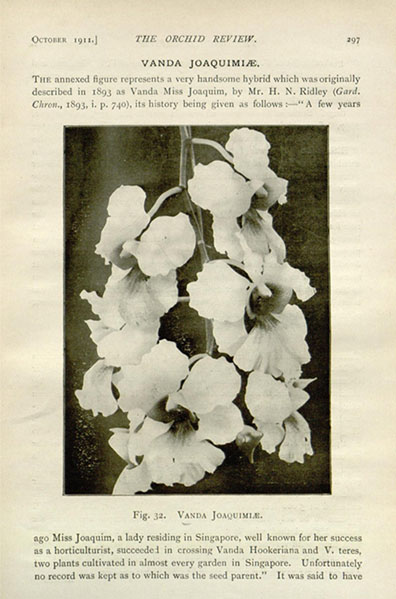

In 1893, Ashken achieved what no other woman had accomplished before. She successfully created a hybrid orchid by cross-pollinating the Burmese Papilionanthe (Vanda) teres with the Malayan Papilionanthe (Vanda) hookeriana. The resulting bloom, with its distinctive pink and purple coloration, represented the first documented orchid hybrid bred in Asia. In 1899, Ashken’s orchid caused a sensation at the annual Singapore Orchid Show. Many observers considered it to be the event’s main highlight, and she won first prize for “rarest orchid.” By then gravely ill, Ashken died three months later of cancer, aged 45. She never married or had children, and did not live to see just how seismic her achievement was.

In 1981, newly independent Singapore selected its National Flower. And the choice was none other than Papilionanthe (Vanda) Miss Agnes Joaquim; Ashken’s hybrid which bears the Anglicised version of her name. Today, this orchid grows prolifically not only across the parks and gardens of Singapore, but across many tropical areas of the world. Little did Ashken know that, one day, her flower would one become a permanent fixture of Singapore’s cultural identity, and that it would bring joy to countless people across the globe.

Seeds of Doubt

The director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Henry Ridley, originally examined this remarkable Ashken’s new flower and officially registered it as Vanda Miss Joaquim in 1893. In his scientific description published in The Gardeners’ Chronicle, Ridley correctly acknowledged that “Miss Joaquim, a lady residing in Singapore… has succeeded in crossing Vanda Hookeriana and V. teres.” He recognised her deliberate scientific achievement in the original documentation.

The distortion of Ashken’s accomplishment came later. In subsequent decades, botanical writers and historians began mischaracterising her achievement as an accidental discovery rather than intentional hybridisation. By the mid-20th century, the narrative had shifted dramatically, with publications claiming she had merely “found” the plant in her garden—effectively erasing her scientific work.

In 1981, Vanda Miss Joaquim was selected as Singapore’s National Flower, becoming a symbol of the nation’s hybrid cultural identity. Yet by this time, the false “accidental discovery” story had long become the accepted account.

Only in the 1990s did researchers, including Nadia Wright and Harold Johnson, begin to challenge this narrative. Later joined by Ashken’s great grandniece, Linda Locke, they returned to Ridley’s original documentation and uncovered evidence proving Ashken had deliberately created the hybrid through careful cross-pollination, confirming what her family had always maintained. Despite articles being published with compelling evidence, the false ‘accidental discovery’ story continued to dominate until the mid-2010’s, when Locke conducted further research and the authorities in Singapore finally conceded that the hybrid was a deliberate creation.

In 2015, the Armenian Heritage Museum in Singapore finally installed a memorial acknowledging Ashken Hovakimian as the breeder—not merely the discoverer—of Singapore’s national flower. Her story exemplifies how historical narratives often marginalise the scientific and cultural contributions of women and non-Europeans over time, and how reclaiming these narratives becomes an act of historical justice.

Today, when Singapore celebrates its National Flower, it increasingly acknowledges the remarkable Armenian woman who created it—a plantswoman whose achievement transcended the limitations imposed by colonial society, even as subsequent historical accounts temporarily erased her scientific accomplishment. Perhaps the most fitting tribute to Ashken’s legacy lies etched in stone at her final resting place in the Armenian Apostolic Church grounds in Singapore. Written years before there were attempts to erase her achievements and nearly a century before her creation became the country’s National Flower, her gravestone bears a simple epitaph which reads ‘Let her own works praise her.’

As her grandniece, Linda Locke, states:

“It is extraordinary that for 80 years from its creation, no one doubted that Agnes Joaquim created the Vanda Miss Joaquim. More importantly, no one doubted Henry Ridley, the first scientific director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens and a world expert on orchids who recognised, named her feat and was published in June, 1893; in the Gardeners’ Chronicle. The naysayers since then have no factual basis for doubt.”

Linda Locke, Great Grandniece of Agnes Joaquim.