0

You have 0 items in your cart

Beyond Slavery

Though slavery was abolished across the Western world in the early 19th century, former slaves continued to live in poverty. Slave owners—not the enslaved—received compensation, while direct slavery was replaced by indirect oppression through resource extraction from European colonies and exploitative industrial labour at home (such as Victorian cotton mills, notorious for their use of child labour).

“Scientific” Racism

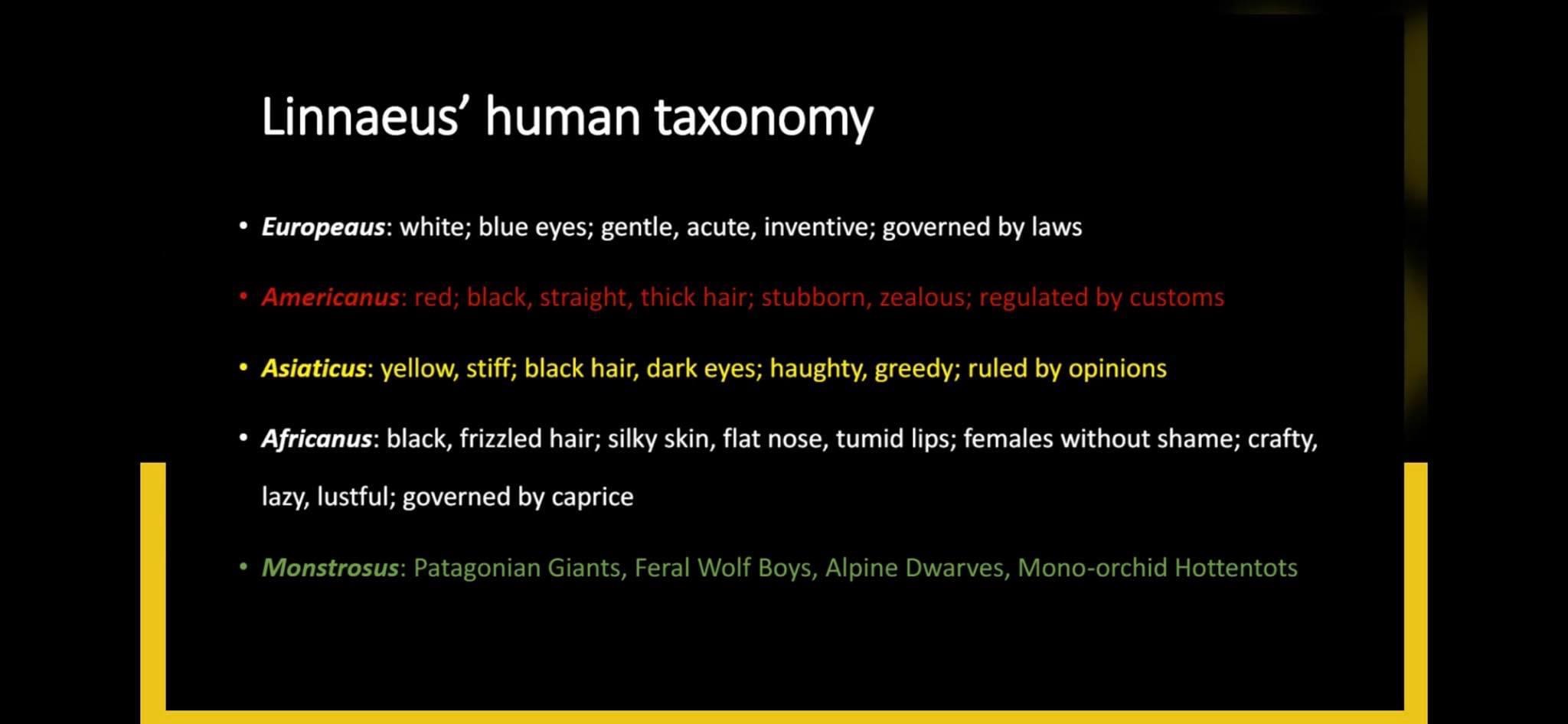

From the 18th to early 20th centuries, eugenics and racial theories dominated Western academic circles. Carl Linnaeus, the ‘Father of Botany’ who described many orchids, was himself one of many who classified “human races” according to racial stereotypes. This thinking permeated society so thoroughly that, for example, even some slavery abolitionists and liberals sometimes maintained beliefs that Black people were “naturally less intelligent” than white Europeans.

Edmond’s Story Through This Lens

Edmond Albius became a victim of this racialised climate. Many Westerners simply refused to believe a young Black boy had discovered what they for decades could not: vanilla’s pollination mechanism. According to prevailing racial hierarchies, Northern Europeans were deemed “superior,” Southern Europeans “lesser,” then “Asiatics” below them, with Black people at the bottom. This was alongside beliefs that “tropical climates” could not produce “intelligent people.”

Until after World War II, these racial theories were mainstream scientific thought. Today we recognise them as harmful pseudoscience. But the fact is that, for centuries, Western science was tainted with what would now be described as racism. This way of thinking persists in some quarters today, and the rejection of Albius’s achievement reminds us that science is not immune to cultural biases. To rise above this troubled past, we must first acknowledge it.

Dino Zelenika, May 2025

Edmond Albius: The Boy Who Revolutionized the Vanilla Industry

Adapted from an article by Leanne Melbourne for The Linnean Society.

Vanilla is one of the world’s most popular spices, and the second-most expensive after saffron. This multi-million-dollar industry owes its existence largely to Edmond Albius (1829–80), a 12-year-old enslaved boy from Réunion Island who developed a practical technique for hand-pollinating vanilla orchids. His ingenious method enabled artificial pollination on a mass scale, creating the global industry we know today. Yet Edmond was never compensated for his revolutionary contribution and died in poverty.

The Vanilla Challenge

The flat-leaved vanilla plant (Vanilla planifolia), native to Mexico, was brought to the Old World in the 16th century by Spanish explorers. As demand for vanilla increased in Europe, cultivators faced a significant problem: plants outside Mexico would rarely produce fruit.

This mystery persisted because of the orchid’s complex flower structure. Vanilla planifolia is hermaphroditic with both male and female parts separated by a membrane that prevents self-pollination. In its native Mexico, specific bees naturally pollinate vanilla flowers, but these pollinators didn’t exist elsewhere.

In 1836, Belgian botanist Charles Morren studied vanilla pollination and published an account of artificial techniques. However, his method was fiddly, best suited to greenhouse conditions, and impractical for plantation-scale production.

Edmond’s Breakthrough

Born into slavery in 1829 in Sainte-Suzanne, Réunion (then called Bourbon), Edmond’s mother died in childbirth and he never knew his father. He was sent to work with Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont on the Belle-vue plantation, who taught him horticulture and botany.

In 1841, while walking through his gardens with 12-year-old Edmond, Bellier-Beaumont discovered fruits on a previously barren 20-year-old vanilla vine. When Edmond revealed he had hand-pollinated the flowers, Bellier-Beaumont was initially skeptical. After witnessing Edmond’s technique—which involved using a thin blade of grass or a bamboo splinter to lift the membrane separating the male and female parts and pressing them together—Bellier-Beaumont recognized its brilliance.

Bellier-Beaumont later wrote: “This clever boy had realized that the vanilla flower also had male and female elements, and worked out for himself how to join them together.”

Word spread quickly. Edmond was transported around Réunion to demonstrate his technique to workers on other plantations. Vanilla production on the island skyrocketed—from 2 tonnes exported to France in 1858 to 200 tonnes by 1898, surpassing even Mexico.

A Life Unrewarded

Despite revolutionizing an entire industry, Edmond’s life didn’t reflect his monumental contribution. When slavery was abolished in French colonies in 1848, he was freed and given the surname Albius. Bellier-Beaumont unsuccessfully attempted to secure him a state pension for his services to the vanilla industry.

At 19, with only a small sum from Bellier-Beaumont, Edmond moved to St-Denis in northern Réunion. Life was difficult—with no formal education and competing with many other freed individuals for limited work. After brief employment as a kitchen boy, he was wrongfully blamed for a robbery, sentenced to five years imprisonment with hard labor, and only released early due to Bellier-Beaumont’s persistent appeals.

Edmond returned to Belle-vue until he married, but his circumstances never improved. He died at age 51 in a public hospital, destitute and unrecognized. As the Moniteur newspaper reported on August 26, 1880: “The very man who at great profit to this colony, discovered how to pollinate vanilla flowers, has died in the public hospital at Sainte-Suzanne. It was a destitute and miserable end.”

Legacy Contested and Reclaimed

Adding insult to injury, some actively tried to discredit Edmond’s achievement. French botanist Jean Michel Claude Richard claimed to have developed the same method years earlier, suggesting Edmond must have witnessed his demonstration. Bellier-Beaumont defended Edmond, noting the timeline made Richard’s claim impossible.

Later historians questioned whether an enslaved person without formal education could have developed such a technique independently. However, thorough analysis by modern researchers concluded: “There is absolutely no reason to believe that Albius could not have figured out all by himself how to pollinate the flowers.”

Today, over 80% of the world’s vanilla is still hand-pollinated using Edmond’s technique. Madagascar—another former French colony where his method was introduced—now produces 40% of global vanilla. While Edmond wasn’t the first to conceive of hand pollination, his practical, efficient technique provided the key that unlocked vanilla cultivation worldwide.

As Bellier-Beaumont remarked about Réunion’s treatment of Edmond: “It owes him a debt, for starting up a new industry with a fabulous product.”

Adapted with permission from “Edmond Albius: the boy who revolutionised the vanilla industry” by Leanne Melbourne, originally published by The Linnean Society (2019).

Link to original: https://www.linnean.org/news/2019/10/16/edmond-albius