0

You have 0 items in your cart

‘What with Jenkins and Simons collecting here – 20 or 30 Falconers, Lobb’s, my friends Lieutenants Raban and Cave and Inglis’ friends, the roads are all becoming stripped like the Penang jungles and I assure you for miles it sometimes looks as if a gale had strewed the road with rotten branches and Orchidaea. Falconer’s men sent down 1000 baskets the other day…’

These words from Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911), later director of Kew Gardens, reveal a façade of environmental concern. Yet in the same expedition, Hooker collected ‘two loads of Vanda coerulea’ requiring seven men to carry the hundreds of plants, most of which died in transit. This contradiction typifies the Western imperial attitude toward natural resources in the Victorian era. In light of this, the above source may instead be read as a mere description of what happened; Hooker was not actually concerned about what he saw.

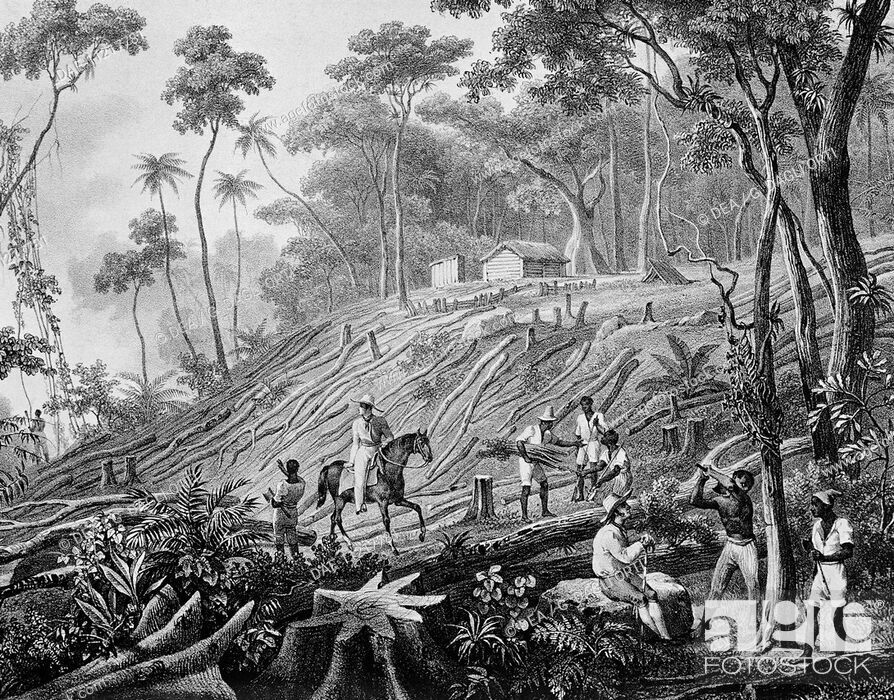

Environmental Destruction as Standard Practice

Throughout the Victorian era, accounts of mass orchid collection reveal environmental devastation that would horrify modern conservationists. Often, it also involved the systematic destruction of ancient jungles. Wilhelm Hennis, collecting in Colombia in 1882-3, describes: ‘I sent some 200 crates of Cattleya trianaei. I have thrown away three times as many plants, those which were damaged either during transit or during the felling of the trees on which they grew.’

This wanton destruction seems incomprehensible today, but notions that nature is ‘beautiful’ and deserving of protection have shallow roots in Western thought. For medieval Europeans, nature was dangerous—full of spirits, hostile beings, and disease. The Scientific Revolution of the late 16th century reconstructed nature as ‘dead and passive, to be dominated and controlled by humans,’ with emphasis on ‘improvement’ and exploitation. It was predominantly this thinking that predominated in Victorian times.

Even the word ‘wilderness’ had negative connotations, associated with desolation and savagery. The concept of wilderness as ‘beautiful’ and worth protecting only began earnestly in the USA in the late 19th century, struggling for acceptance until well into the 20th century. In Victorian Britain, orchids were simply another imperial commodity ripe for exploitation.

Indigenous Exploitation

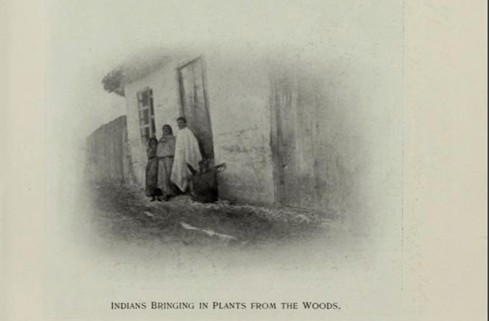

The environmental damage was matched by exploitation of indigenous people. Collection reports reveal precisely how locals were extensively utilised by Western collectors and educated about which orchids were valuable:

‘They know what Europeans are likely to want… A collector does not generally roam at large in these days. Reaching the ground, he makes his bargain with the natives; ten cents to a dollar in money or goods, according to circumstances, for every specimen, big or little.’

Robert Fortune described in 1847 how he established headquarters in ‘an Indian’s hut in the wood…where I held a sort of market for the purchase of orchids.’ For one massive Phalaenopsis amabilis specimen—reportedly the largest ever sent to Europe—Fortune paid just one dollar. The Duke of Devonshire had previously paid 100 guineas (approximately £9,533 today) for a much smaller specimen.

This exploitation reflected the Western imperial belief in environmental determinism—that warmer climates produced less civilised people—which legitimised colonial expansion. Indigenous people were frequently described with pejoratives such as ‘savages,’ with no concern for their welfare or the risks they undertook collecting orchids and other commodities.

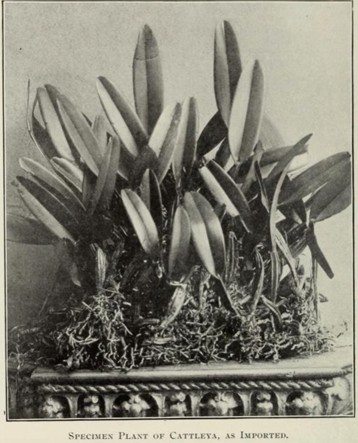

Above: photograph from a 1905 catalogue of an American importer of orchids, and some of the wild collected orchids as imported. During this period, “imported” also meant “wild collected”

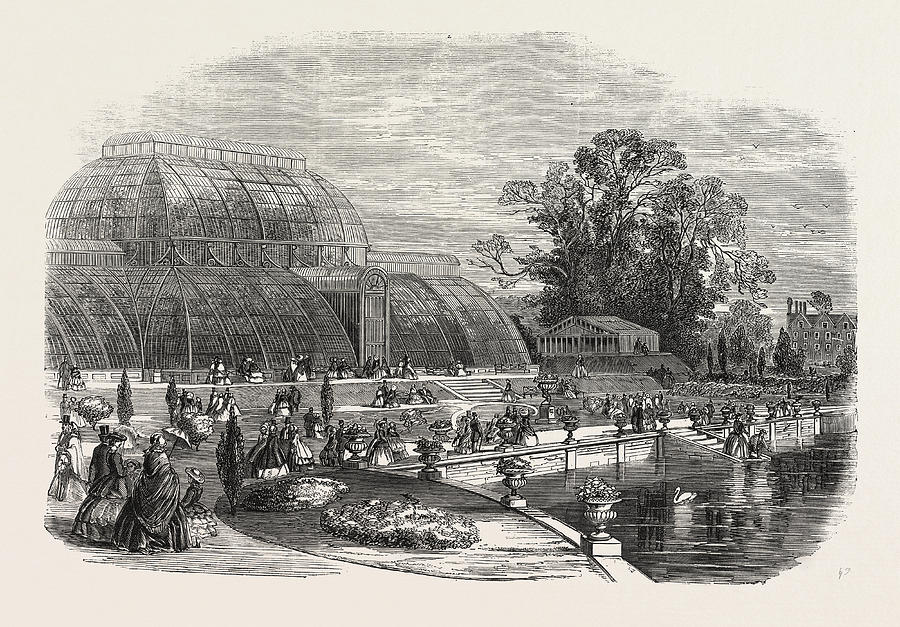

Imperial Botany and Institutional Support

Behind the orchid hunters stood Britain’s powerful botanical institutions. Since 1802, the Royal Horticultural Society and Kew Gardens actively supported colonial collectors, with orchids considered “the great prize.” This practice exemplified “Imperial Botany”—the systematic exploitation of colonial territories for botanical specimens and economically valuable plants.

When Kew became a state institution in 1841, it was explicitly tasked with “aiding the Mother Country in everything useful in the vegetable kingdom” and coordinating colonial botanical gardens. Scientists of this era prioritised specimen acquisition for study and classification over environmental preservation. The concept of conservation simply didn’t exist in their worldview; nature was a resource to be catalogued and utilised.

Directors like William Jackson Hooker regularly advised commercial nurseries on promising collecting locations, effectively directing the imperial extraction of botanical resources. In addition, the establishment of botanical gardens in British colonies was done to aid extraction of wild plants in what was a coordinated imperial system with scientific institutions at its centre. While this institutional role has been studied for commercial crops, its significance for ornamental plants like orchids has been largely overlooked.

Above: Engraving of the Palm House at Kew Gardens, 19th century

Early Environmental Concerns

By the late 19th century, some voices began expressing alarm at habitat destruction. Charles Brooke, the second ‘White Rajah’ of Sarawak, introduced measures in 1893 to prosecute wildlife collectors in response to the disappearance of ‘once abundant’ flora and fauna.

However, such concerns remained rare exceptions. Just two years before Brooke’s crackdown, British newspapers proudly reported on Albert Millican’s collecting in the Andes: ‘Thousands of trees have then to be cut down for the sake of the Cattleya mendelii that festoons them, a flower born in the purple, and much more magnificent than SOLOMON in all his glory.’

The report portrays Millican as courageous for navigating ‘woods as haunted by snakes and savages with poisoned arrows.’ Environmental damage and exploitation of indigenous people were afterthoughts compared to the glory of obtaining rare orchids for Britain’s wealthy collectors.

Legacy of Destruction

The business model of Victorian nurseries relied entirely on wild importation, charging prices exponentially higher than what indigenous collectors were paid. This pattern of exploitation—both environmental and human—continues to echo in modern conservation challenges facing orchids today.

As you explore our “Orchid Obsession” exhibit at Chelsea Flower Show, consider how contemporary attitudes toward orchid conservation reflect a dramatic shift from these Victorian practices, yet how their legacy of exploitation continues to shape global orchid trade and conservation efforts.